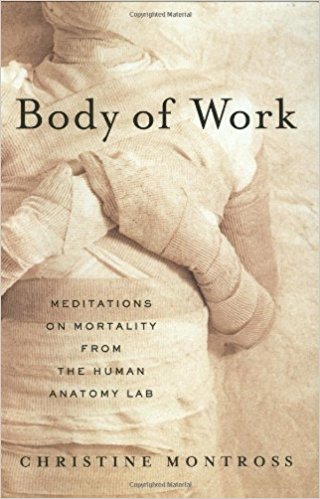

Body of Work

When I asked you to choose my next non-fiction adventure and the votes started rolling in for The Island at the Centre of the World – mor cast a phone vote – I discovered that after all that, I did know what book I wanted to read and it was Body of Work: Meditations on Mortality from the Human Anatomy Lab

by Christine Montross. Naturally, I then engaged in a clever (?) bit of subterfuge and a deep cover agent volunteered to stuff the ballot box. The good news is that I didn’t have to – Body of Work squeaked by to win with one (real) vote. I do think that regardless of how bad I am at lying – and I’m very, very bad – I’d have problems convincing you that Jeffery Deaver, Mary Roach

and Jessica Sachs all read my blog… (p.s. maybe my undercover agent can enlighten us about Jessica Sachs – I’m not sure who she is)

Moving onto the book. Although I am going to get more verbose about it, it can be summed up neatly in the following two sentences: I know things now that I didn’t know I wanted to know. I also know things that it turns out I most emphatically did not want to know, but am nonetheless glad I now do.

T he book is, as the title indicates, a memoir of medical school, anchored in the experience of what apparently is called cadaveric dissection in the first year anatomy course. Chapters are built around each module of dissection – torso, stomach, pelvis, head, etc. – but within each chapter, the narrative flows from the lab, to the history of dissection (including the resurrectionists and Burke and Hare), to attitudes towards death in different cultures, to Montross’ life, reactions and thoughts. She does this so effortlessly that I didn’t notice how until chapter 9, but kept thinking “how’d she end up in Bologna looking at wax dissection models from the 18th century?” or weeping my way through an especially heartwrenching passage would wonder how I got there when we’d started out dissecting veins or stomachs.

And speaking of dissection, which given the book we’re talking about, we must. Montross several times uses the term “barbaric” when describing the tasks necessary in dissecting a human body to the point of there being almost nothing left. And barbaric it certainly is, causing deep reactions in the students (and the reader), reactions of such magnitude that studies have described a high number of dissection students to experience symptoms of PTSD. Woven throughout the book is the thought: is this necessary? And the more I thought about it, the more I agree it is.

Apparently, the goal is for a doctor to develop what’s called ‘detached concern’ – the desire and willingness to help, without emotional involvement that will get in the way of the job. Cadaveric dissection aids in this goal as it begins to desensitize the student from the natural emotions you feel when dealing with people in distress. Besides, the practical part of me believes it’s important to actually get your hands into a body (as opposed to a computerized simulation) – how else could you practice such an unnatural act so you don’t freak out when the time comes to doing it on a live person?

When writing this review, I kept wanting to sidetrack into discussions of the 57 (at least) things I want to learn more about after reading this book. For instance – where the bodies for dissection comes from determines the students’ attitude towards “their” body and the emotional reactions to dissection. In Thailand, donation is rare and medical schools require students to honour their body deeply, to know his/her name and to be directly involved in its cremation. In Nigeria, bodies are those of executed criminals and subsequently lose their humanity in lab.

I also learned that dermatology and ENT are highly competitive fields and remain puzzled about Ear, Nose and Throat being so desirable a field (anyone out there who can enlighten me?), I learned why my TMJ comes from shoulder (not jaw) problems, that such a final thing as death can be incredibly hard to define and I could go on for hours.

Montross is a terrific writer – her background as a poet shows and makes this book about the poetry of medicine. She can educate you about the miraculous workings of the body, being factual in one sentence and move you with unbearable poignancy in the next. She doesn’t shy away from telling you just why dissection wreaks such an emotional toll, making you want to turn away, then tells you about learning to treat patients with empathy, tenderness and honour and you want to come closer.

This is my favourite kind of book – the author sends out strand after strand of diverse ideas, thoughts and topics and somehow, magically it feels, pulls them all together in the end, when she describes her feelings towards “her” cadaver, the feelings of gratitude, respect and honour (there’s that word again) towards the person who gave her the gift of learning to heal while taking their body apart.

Certainly, it’s a book to be read in segments. Not just because you need to walk away and think after every chapter – again, my favourite kind of book – but, quite frankly, so you can go away and repress what you read. Not for the faint of heart, it is nonetheless a book I’d highly recommend. Partly for the knowledge that is gained, but also because it made me think more deeply about death and dying and ultimately about whether I’d donate my body. Would you?

Montross ends the book with what I assume is the prayer said by Thai students to their body and so will I:

Great Teacher, I give you flowers

I carry your body to the funeral pyre

When you burn, may every space in you that I have named

Flare and burst into light

It was a terrific choice – thanks for voting!

Tag:

Read More

Discover what else I've been writing about...